#01-#52

⚪️ One poster a week to record points of interest when reading about human & non-human interactions ⚪️

#01

Survival of the Cutest

Analysis published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [PNAS] has found that more than 500 species of land animals are on the brink of extinction and likely to be lost within the next 20 years. In comparison, the same number of species were lost over the WHOLE of the last century [100 YEARS]. We often hear about increasing numbers of charismatic megafauna, such as the @wwf announcement that wild tiger numbers are increasing for the first time. However, what we often don’t see or hear about, are the many species that are being pushed to a critical point, that perhaps don’t look as cute on the poster..

Resource: PNAS Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. Gerardo Ceballos, Paul R. Ehrlich & Peter H. Raven. June 16, 2020.

#02

Living with Pests

![]()

As agents operating within the natural world, we need to re-evaluate our preconceptions of the ‘pest’. We might champion the success of species conservation globally but, what use are these successes if we hold a blatant disregard for the rapid habitat loss on our front door step? We complain about defecating bats, though they are the main predator of disease-harbouring mosquitos. We remove beehives and ward off bees, despite the fact that bees pollinate over 90% of the world’s wild vegetation and over 30% of the world’s crops. Not only are bat & bee populations declining in urban environments, but they are also endangered in rural areas. Natural pollinators are struggling due to the increasing use of chemical pesticides. If we continue to regard certain species as ‘pests’ (and in turn, a disposable part of our ecosystem) we only contribute towards the current ecological crises.

As a designer, I am practicing within a landscape of shifting cultural and ecological values. I must not only develop outcomes that integrate wildlife habitat & biodiversity into the built environment but, I need to also take on the challenge to rethink the spatial & cultural dimensions in which urban animals and organisms may exist. In doing so, this should enable urban inhabitants to envision the possibility of a truly biodiverse urban landscape, one which there is space for all species to co-exist.

Resource: Volume #35: Everything Under Control

#03

We Need Solitary Bees

In the age of the Anthropocene, the importance of bees - and other pollinators such as butterflies and moths - has become more apparent than ever, with more than 75% of the world’s food crops and 35% of global agricultural land depending on animal pollination. However, bee species are under threat, with current extinction rates being 100 to 1,000 times higher than normal due to human impacts, according to the United Nations. Intensive farming practices, land-use change, mono-cropping, pesticides and higher temperatures associated with climate change all pose problems for bee populations and, by extension, the quality of the food we grow. How can we do more as individuals?

1. Planting a diverse set of native plants, that flower at different times.

2. Buying products from sustainable agricultural practices.

3. Avoid pesticides, fungicides or herbicides in the garden.

4. Protecting wild bee colonies where possible.

5. Providing suitable habitat in outdoor spaces.

Resource: UNITED NATIONS: We all depend on the survival of bees (www.un.org/en/observances/bee-day)

#04

The London Underground Mosquito

Currently reading Menno Schilthuizen’s captivating book ‘Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution’.

One study in the book, (Katharine Byrne, 1999) demonstrated that the underground mosquitos on three tube lines were found to be genetically different from one another. The only way for the mosquitos in the Central, Bakerloo and Victoria lines to become genetically mixed, would be “for all of them to change trains at Oxford Circus station”.

It was later found that the underground species of mosquito was not unique to London and it lives in cellars, basements and subways all over the world. The reason perhaps that we are so captivated by such a story, however, is that it demonstrates urban evolution is happening right here on our doorstep. The notion that ‘wild’ animals are adapting to environments that we have created, further cements that we are causing irreversible changes to the planet. What if the Underground mosquito is representative of all flora and fauna that come into contact with humans and the human-crafted environment? What if our grip on the Earth’s ecosystems has become so firm that life on Earth is in the process of evolving ways to adapt to a thoroughly urban planet?

Resource: Byrne, Katharine & Nichols, Richard. (1999). Culex pipiens in London Underground tunnels: Differentiation between surface and subterranean populations. Heredity. 82 ( Pt 1). 7-15. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6884120.

Resource: Schilthuizen, Menno. (2018). Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution. Edition published 2919 London: Quercus Editions Ltd.

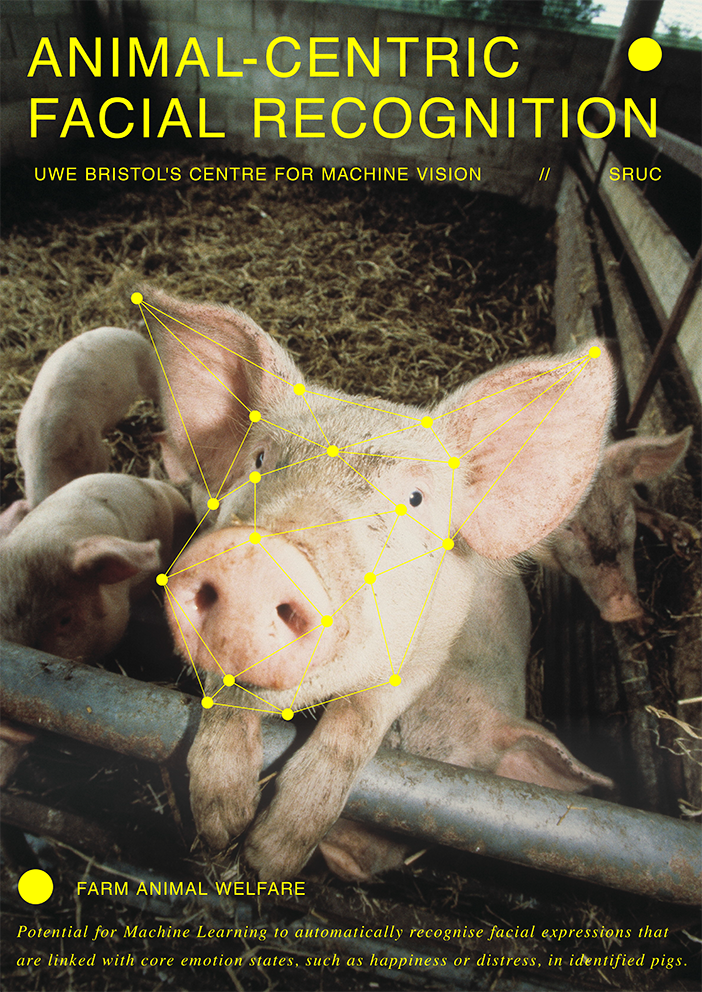

#05

Animal-Centric Facial Recognition

I recently watched the Netflix documentary ‘Connected’. In the surveillance episode, which could be described as Animal Farm meet’s 1984 (or George Orwell’s worst nightmare), presenter Latif Nasser shows viewers around a “Piggy Facial Recognition” research centre. The project, run by UWE Bristol’s Centre for Machine Vision and Scotland’s Rural College, sees AI and facial recognition software correctly identify the face of a pig with 97% accuracy.

Their next step is to introduce recognition of facial expressions, in order to answer important animal welfare questions such as; is this pig stressed? Is this pig in pain? Being able to recognise such emotions is likely to improve the overall welfare for farm animals, removing the need to mutilate through ear tagging and giving the pigs more individualised healthcare attention.

I also viewed the project as a potential tool to engage us with the inner consciousness of other sentient beings. In anthropomorphising and empathising with captive animals, might we consider them to have a higher intelligence or level of consciousness than previously understood?

Or, naively, perhaps this is just another commercial tool to ensure the intensive farming industry can continue on a mass scale. What are your thoughts?

Resource: Connected, 2020. [TV programme] Netflix.

Resource: https://blogs.uwe.ac.uk/research-business-innovation/facial-recognition-technology-aims-to-detect-emotional-state-in-pigs/

#06

Magical Melanism of Manchester’s Peppered Moths

Further highlights of Menno Schilthuizen’s book ‘Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution’ is the story of Manchester's peppered moth. First emerging in nature as a pale, white-winged insect, by the middle of the Industrial Revolution, the moth's wings had evolved to be coal black. The reason? To better blend in with the soot produced by the city's factories. The dark-winged moths were less visible to bird attacks than their white-winged siblings, so natural selection ultimately favored the former. What’s most surprising though, is how quickly the process of evolution happened, as it was previously thought such changes happened over millions of years.

Albert Brydges Farn, a lepidopterist, first observed the effects of ‘industrial melanism’ in the annulet moth in the late 1800’s, long before it was more famously seen in the peppered moth. In an interesting twist, a letter was discovered in 2009, dated 18th November 1878, showing that Farn wrote to Charles Darwin about his discovery. Darwin, however, did not respond, as he didn’t believe that natural selection could actually be observed in real time. Perhaps this was because he lacked the mathematical prowess to calculate exactly how long it would take for natural selection to do its thing, whereas Farn had in fact seen the evidence of the moth’s changes with his own eyes.

Resource: Schilthuizen, Menno. (2018). Darwin Comes to Town: How the Urban Jungle Drives Evolution. Edition published 2919 London: Quercus Editions Ltd.

#07

Animal Crossing(s)

![]()

The roaring sound of road traffic doesn’t stop big mammals from crossing a highway - nor does it sway smaller creatures from being squashed. In just two years along one stretch of highway in Utah, 98 deer, three moose, two elk, multiple raccoons, and a cougar were killed in car collisions—a total of 106 animals. In the United States, there are 21 threatened and endangered species whose very survival is threatened by road mortalities, including Key deer in Florida, bighorn sheep in California, and red-bellied turtles in Alabama.

“It’s estimated [that] one to two million large animals [are] killed by motorists every year,” says Rob Ament, WTI.

There’s one solution, however, that’s been remarkably effective around the world in decreasing collisions between cars and animals crossing the road: wildlife under- and overpasses. Studies that looked at a cross-section of native species' deaths on highways in Florida, bandicoots and wallabiesin Australia, and jaguars in Mexico, just to name a few, all show that wildlife crossings save money and lives, both human and animal.

“You can get reductions of 85 to 95 percent with crossings and fencing that guide animals under or over highways,” Ament says.

Resource: VARTAN, STARRE. (2019). How wildlife bridges over highways make animals—and people—safer. PUBLISHED APRIL 16, 2019, National Geographic

Resource: Google Maps